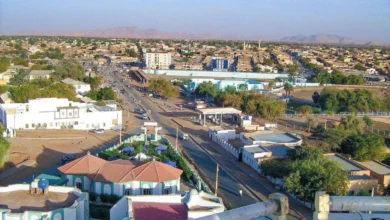

The Sudanese capital, Khartoum, has undergone profound cultural and social transformations since the outbreak of war. Cafés that once served as platforms for discussion and expression have gradually disappeared, while theaters and cinemas have ceased operations, leaving many public spaces deserted. This transformation raises pressing questions about the city’s future and its cultural identity amid the loss of landmarks that once formed part of its collective memory.

Until 2022, Khartoum was home to more than 45 cultural cafés, which hosted poetry readings, art events, and weekly intellectual discussions, according to unofficial figures from independent cultural associations. But since the war began, most of these venues have shut down due to the destruction of infrastructure and the mass displacement of residents.

Stories and Conversations

Writer Suleiman Mohamed explained that “cultural cafés were the soul of the city — not merely places to drink coffee, but spaces where people breathed ideas. Friendships were formed, texts were born, and debates flared up that could never happen within official institutions.” He continued, “The absence of these spaces isn’t just a recreational loss; it silences the city’s voice. Khartoum without intellectual cafés is a city without mirrors — it can no longer see its own face or hear its echo.”

Cultural activist Rania Jamil shared a similar view, saying, “Cultural cafés weren’t just places to sit and chat — they were a living, open archive of the city. Every table held a story, and every poetry night or political discussion documented a moment in Khartoum’s history.” She added, “What we’re witnessing now is a rupture in the city’s daily memory. When such spaces close, informal communication between cultural actors breaks down, and the shared creative atmosphere that once defined Khartoum begins to fade.”

She went on to say, “Walls can be rebuilt, but restoring the city’s spirit takes time — and the return of those spaces that once wove together Khartoum’s cultural and social fabric.”

Temporary Shelters

Playwright Jibril Abdullah recalled, “Before the war, Khartoum had more than a dozen active theaters — including the National Theatre, Al-Mahdi Dome Theatre, and the Folk Arts Theatre — with weekly performances attended by diverse audiences. When the conflict broke out, all shows stopped, and some venues became temporary shelters, while others were directly damaged.”

He continued, “In Khartoum, theater was never just entertainment — it was a forum that reflected the pulse of the street and offered critical insight into social and political issues. We worked with limited resources but great passion, and our halls were full even in the tensest of times.”

“Since the war began, everything stopped — rehearsals, performances, even small meetings in community halls. Many actors and writers have been displaced or scattered. Performing before a live audience has become a distant dream. But I still believe theater never dies. There are individual efforts in exile, online performances, and scripts being written with hope. The theatrical spirit remains — waiting for a safe space to breathe again. The old theaters may not return as they were, but new ones will rise, built on memory and loss, telling a different story of what we’re living through.”

Disappearing Landmarks

According to estimates from urban heritage organizations, around 70% of Khartoum’s open landmarks have gone out of service since April 2023.

Urban historian Ammar Adam explained, “Public landmarks aren’t just recreational sites — they are pillars of collective memory. These squares and open spaces were part of people’s daily routines and of the national scene as well. When such places disappear or fall into neglect, a subtle erosion of belonging begins. A place is not just geography — it’s a carrier of symbols, events, and shared rituals.”

He added, “In some countries, post-crisis recovery began with restoring public spaces — because they rebuild trust and reassurance. I believe reviving Nile Street and Freedom Square should be a top priority after the war, given their national symbolism.”

A Silent Space

Visual artist Mohamed Bashir said, “Before the war, we held open-air exhibitions along Nile Street, painted murals in Al-Qurashi Park, and used Freedom Square for collaborative art projects. Today, those spaces are completely silent — some have even lost their defining features.”

He added, “We’re now working individually to archive old photographs and paintings that document these spaces so they won’t vanish from collective memory. Visual art can help us reclaim what we’ve lost — even temporarily — on paper, canvas, and in the digital archive.”

A New Chapter

Despite the collapse of Khartoum’s cultural infrastructure and the decay of much of its urban landscape, new individual and collective initiatives have emerged among creators and activists in displacement areas and exile. Through documentation, writing, and symbolic events, Khartoum struggles to hold on to its cultural essence despite visible decay.

Cultural writer and researcher Ahmed Al-Fadil explained, “Throughout its history, Khartoum has lived through similar moments of disruption and tension — but it always returned, carried by its people, not institutions. What’s happening now isn’t the end of the city, but a new chapter in its silent resistance.”

He added, “Cultural identity isn’t built only in theaters or on sidewalks — it lives in daily details, in people’s language, in how they narrate their experiences, no matter how ordinary or painful.”

“The new generation is writing, filming, and archiving — not from the city center, but from its margins and from exile. These efforts may not have an immediate impact, but they preserve memory from total erasure.”

Rehabilitation Efforts

Meanwhile, Mohamed Ahmed, an official at the Ministry of Culture, stated, “We are fully aware of the extensive damage that has hit the cultural infrastructure — especially theaters and performance venues that once thrived in the capital. At present, we are documenting the damage and drafting plans for rehabilitation once the security situation stabilizes.”

He added, “The cultural sector will be a key component of Sudan’s broader recovery process, as we believe that the revival of cultural life is essential for restoring social balance. We have a digital archive of scripts and performances, and we’ll work to revive cultural events with support from local and international partners.”