Sudanese civilians trapped amid fierce fighting between the army and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), and deprived of the most basic means of survival, are struggling to endure in besieged western cities cut off from any form of aid.

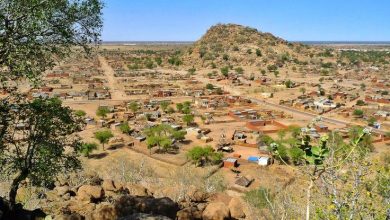

The war in Sudan has entered its third year, claiming tens of thousands of lives and causing famine that afflicts millions of civilians stranded in besieged cities deprived of humanitarian assistance, where diseases and epidemics are spreading. Agence France-Presse spoke with residents of three cities surrounded by RSF forces attempting to wrest control from the army inside them — El Fasher, the capital of North Darfur; Kadugli; and Dilling in South Kordofan. The following are testimonies from survivors interviewed by the agency.

“Everything is gone”

“In El Fasher, the shelling continues all day long, so most of the time we stay inside shelters we dug near our homes,” said Omar Adam, who fled from Abu Shouk camp on the outskirts of El Fasher to the Al-Daraja neighborhood in the city’s north. He described unsafe makeshift shelters dug by civilians in public squares and in front of homes to protect themselves from bombardment.

In recent months, the RSF has intensified attacks on army-held areas in the west and south after the army secured control of key cities in central and eastern Sudan. The RSF has besieged El Fasher for more than 500 days — a city of around 260,000 civilians, half of them children — with almost no humanitarian aid, according to the United Nations.

Adam added, “Everything here is gone, even ambaz,” referring to a type of livestock fodder made from sesame and peanut husks. He explained that leaving El Fasher has become extremely expensive and dangerous.

UN Humanitarian Coordinator in Sudan, Denise Brown, stated last week that there were “reports of unlawful killings, abductions, and arbitrary arrests” of civilians attempting to leave El Fasher.

A wall around El Fasher

Satellite images analyzed by the Humanitarian Research Lab at Yale University show that the RSF has built a 68-kilometer wall around El Fasher, leaving only one exit where civilians are extorted for money to pass.

Halima Issa, a mother of three who lost her husband in an artillery strike, said her family relies on meals from tekkiya — public kitchens offering free food. “When the tekkiya stops working, we don’t eat. If one of the children gets sick, there’s no treatment,” she said.

According to the El Fasher Resistance Committees Coordination, the price of ambaz has surpassed two million Sudanese pounds (around USD 600), a price far beyond what most families can afford.

From El Fasher hospital — one of the few medical facilities still functioning after most of the city’s health infrastructure was destroyed — a doctor, speaking anonymously for security reasons, said he has been working continuously for three months. “There’s a shortage of medicine — even the gauze we use to cover wounds is gone,” he said.

“We now use mosquito net fabric to bandage wounds,” he added, “and sterilizing medical tools for treating injuries and removing shrapnel has become nearly impossible without disinfectants.”

The El Fasher Resistance Committees described the city as “an open-air morgue bleeding from all sides,” saying in a statement this week: “Shells rain down like water, leaving bodies pulled from under the rubble without names or faces — just numbers in a long record of massacres.”

Nearly empty pharmacies

Hassan Ahmed, a volunteer doctor at a children’s hospital, said, “People die in front of us every day — cases that would have been easily treatable under normal circumstances. There are no medicines, and pharmacies are nearly empty.”

In South Kordofan, the RSF has imposed a siege on Kadugli, where residents now survive on “one meal a day — and on many days, none at all. We resort to eating tree leaves and wild plants,” said 28-year-old Hajar Jumaa.

The RSF and its allies have also surrounded the city of Dilling. A resident, Mujahid Musa, 22, said, “Prices double every day — most families can no longer afford to buy food.” Many residents have fled the besieged city, ending up as refugees in nearby villages.

Volunteer relief worker Sadiq Issa reported that security forces seized a shipment of children’s biscuits sent by UNICEF — referring to the army, which allegedly sold the supplies in local markets. He and other witnesses also said that the army had withheld a World Food Programme aid shipment instead of distributing it to those most in need.